So it goes

10 minute read

When I was applying to graduate school and asking for letters of recommendation from my undergrad professors, one of them told me to give academia three years, and that if I hadn’t found a permanent position by then, to find another career. It’s been three years, and next week I start a new job as a data scientist. I read a fair bit of quit lit in my first couple years of grad school and always told myself that if I went that same route, I would never pen any of my own…

Two things have changed since then. One: an already precarious academic job market that never recovered from the global financial crisis has imploded even further. Two: opportunities for people with the set of skills you pick up in a quantitative social science PhD program have exploded. Quit lit is often deeply personal and centered around the path one took to deciding to leave academia; see this piece for links to several prominent examples.1 This is not that kind of quit lit, because that’s not where my communication skills are strongest. Instead, I’m writing this post to illustrate the contrast between my academic and nonacademic job search processes in the hopes that it may be a useful data point for current grad students, postdocs, adjuncts, and maybe even some early-career faculty.2 When reading this post, bear in mind that I am presenting data from an n of one, and my experiences may not generalize outside of quantitative social science, or even very far within it.

I had an enormous amount of support in this process from both my institutions and my networks; in no way could I have gotten a data science job as easily on my own. I talk more about the help I received in this post.

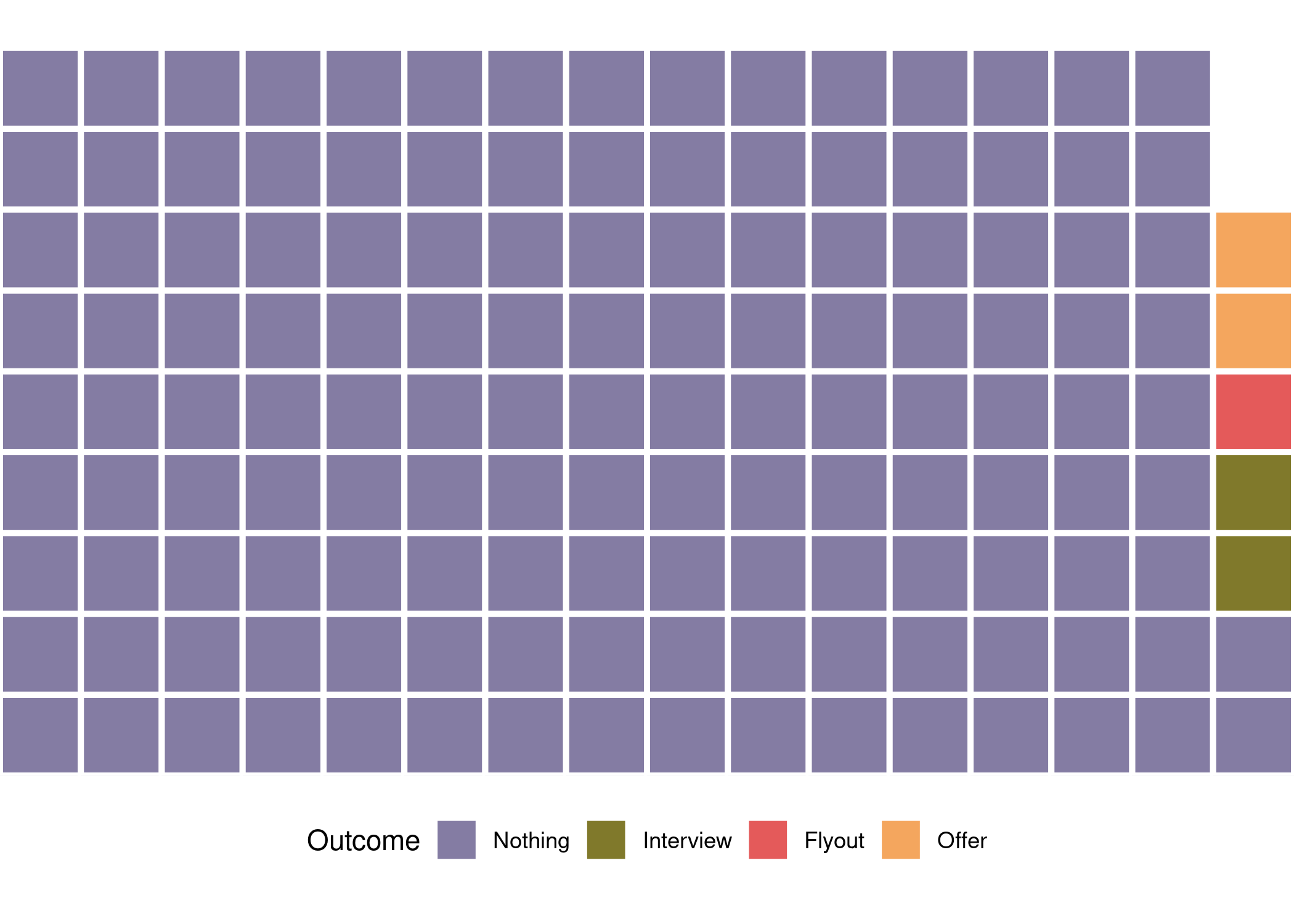

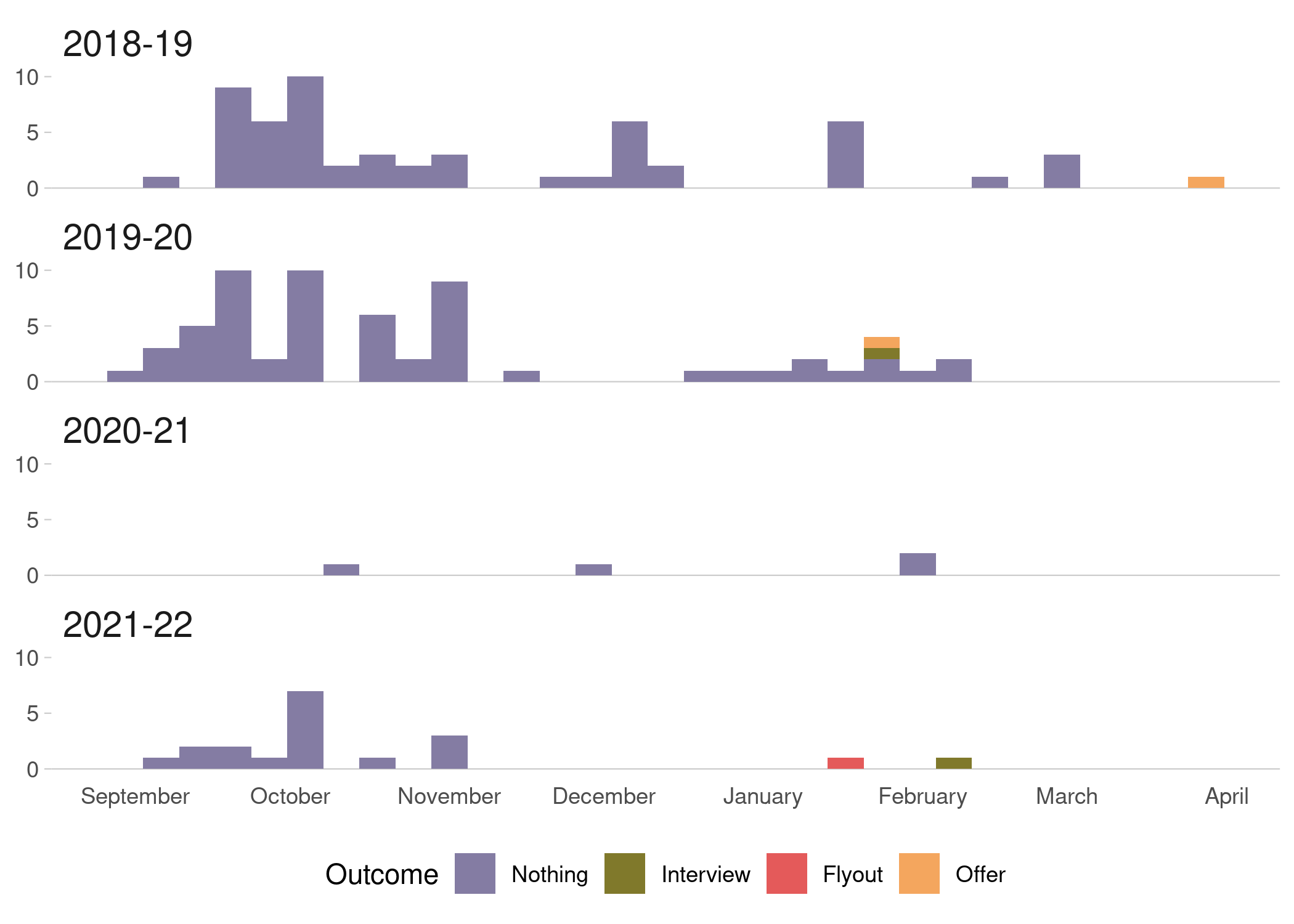

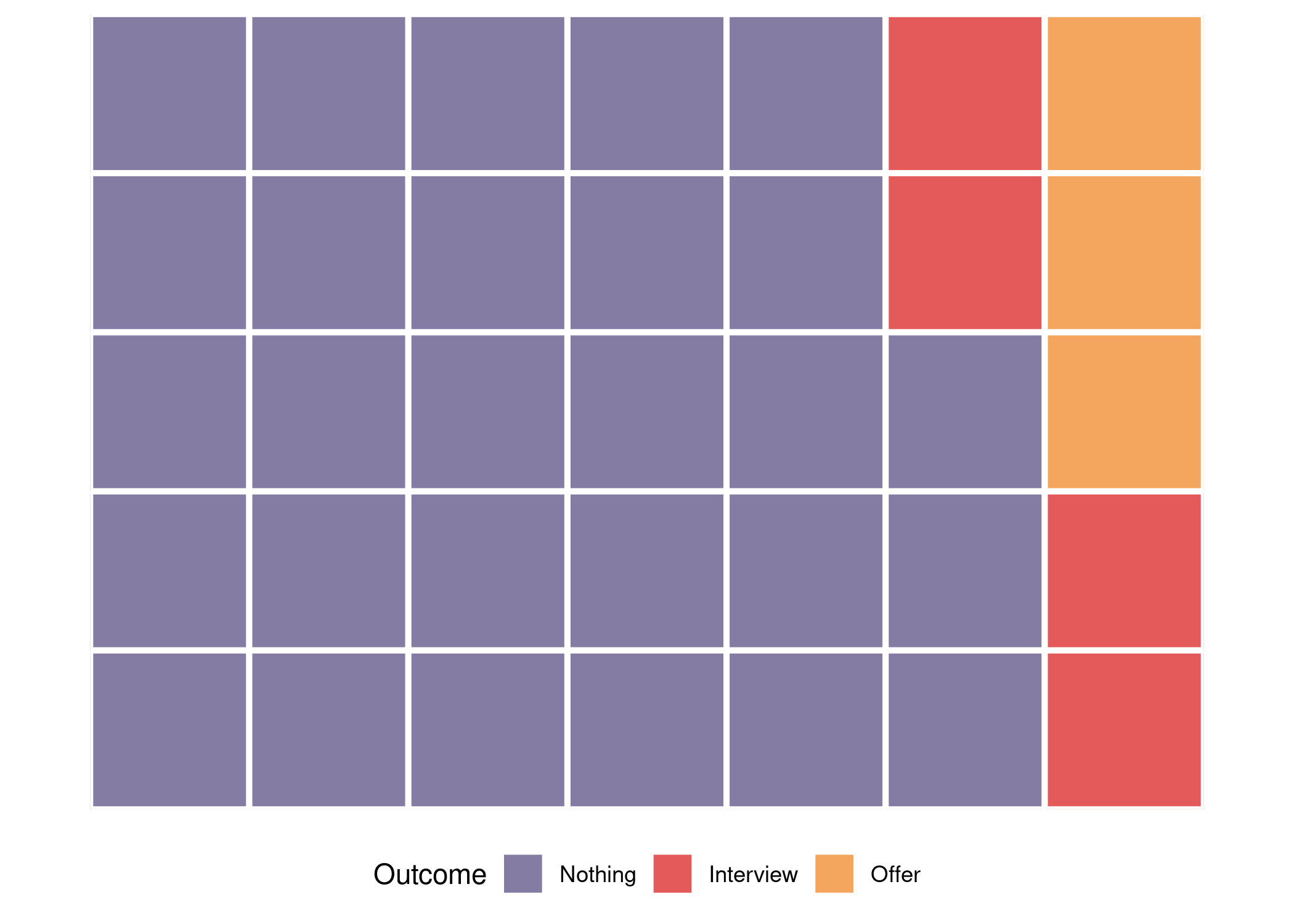

Let’s get straight to the numbers. Out of 142 jobs I applied to, I received two job offers. That’s a 98.6% rejection rate.3 Visualizing this (with apologies to Andrew Heiss) looks like so.

Five jobs expressed interest me beyond my initial application, which translates to a 3.5% response rate. The ‘Nothing’ category encompasses both jobs that sent me an automated HR rejection email (often several months after their chosen candidate had accepted the offer) as well as ones that never got back to me. Many searches for faculty positions will conduct Zoom/Skype/Teams interviews with their long short list of candidates before inviting the short list to an on-campus visit, colloquially termed a flyout, but some may skip straight to the on-campus visit. Some postdoc positions conduct virtual interviews, while others simply make an offer to their preferred candidate. I used a rough ranking of potential outcomes as Offer > Flyout ≥ Interview > Rejection in constructing this plot, with each dot representing the final outcome for that application.

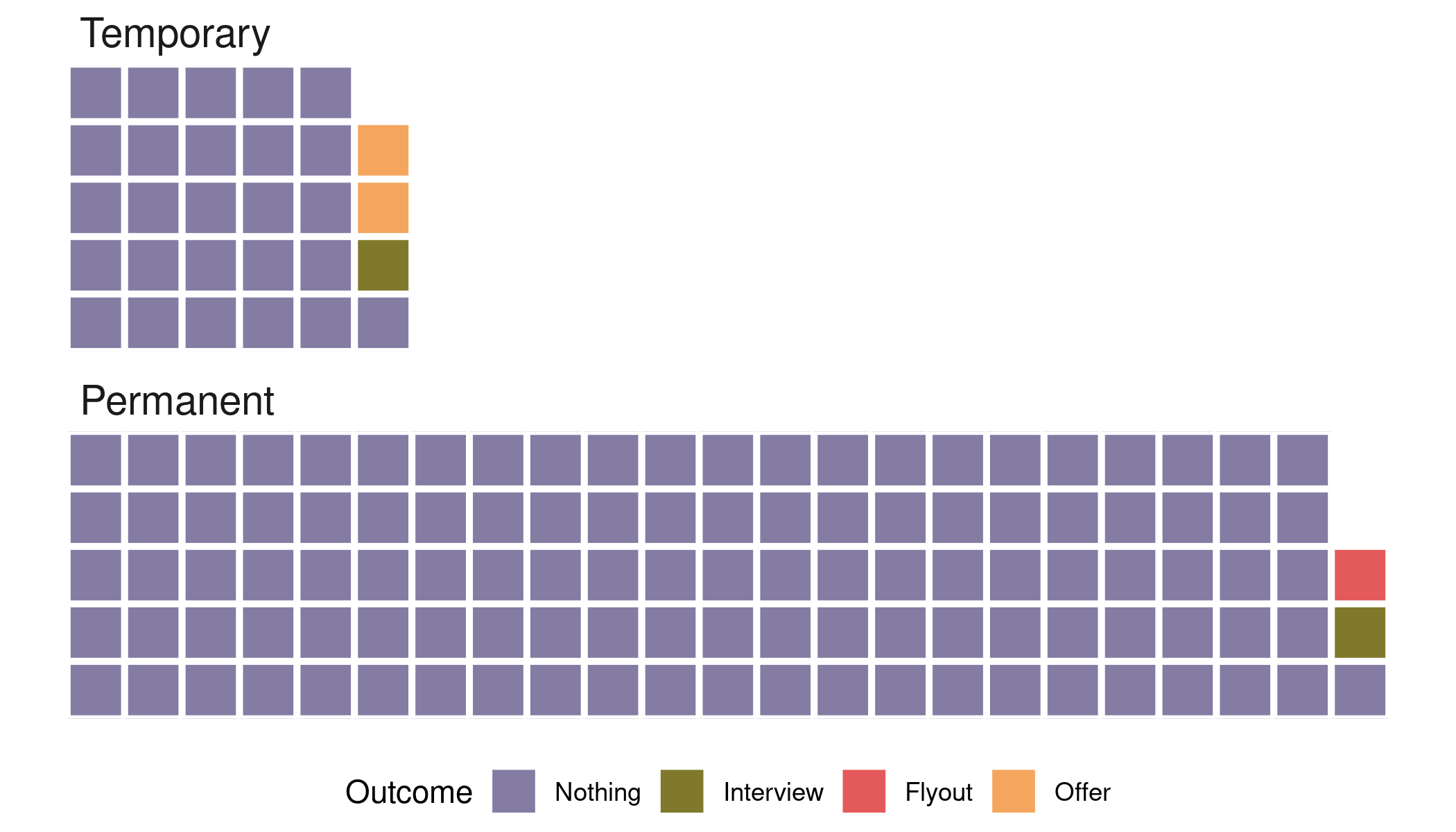

I applied to a wide range of permanent (tenure-track and teaching-track) faculty positions, as well as a number of temporary (postdoc, visiting assistant professor, lecturer) positions. Splitting my applications along this dimension shows that I had noticeably more success in my applications for temporary positions (10.3% response rate) than permanent ones (1.8% response rate).

Since my non-nothing outcomes are so few, I can easily list them in more detail:

- Two postdoc offers

- A postdoc I interviewed for and declined in favor of another postdoc offer

- A teaching-track flyout I declined in favor of a data science offer

- A tenure-track interview I declined in favor of the same offer

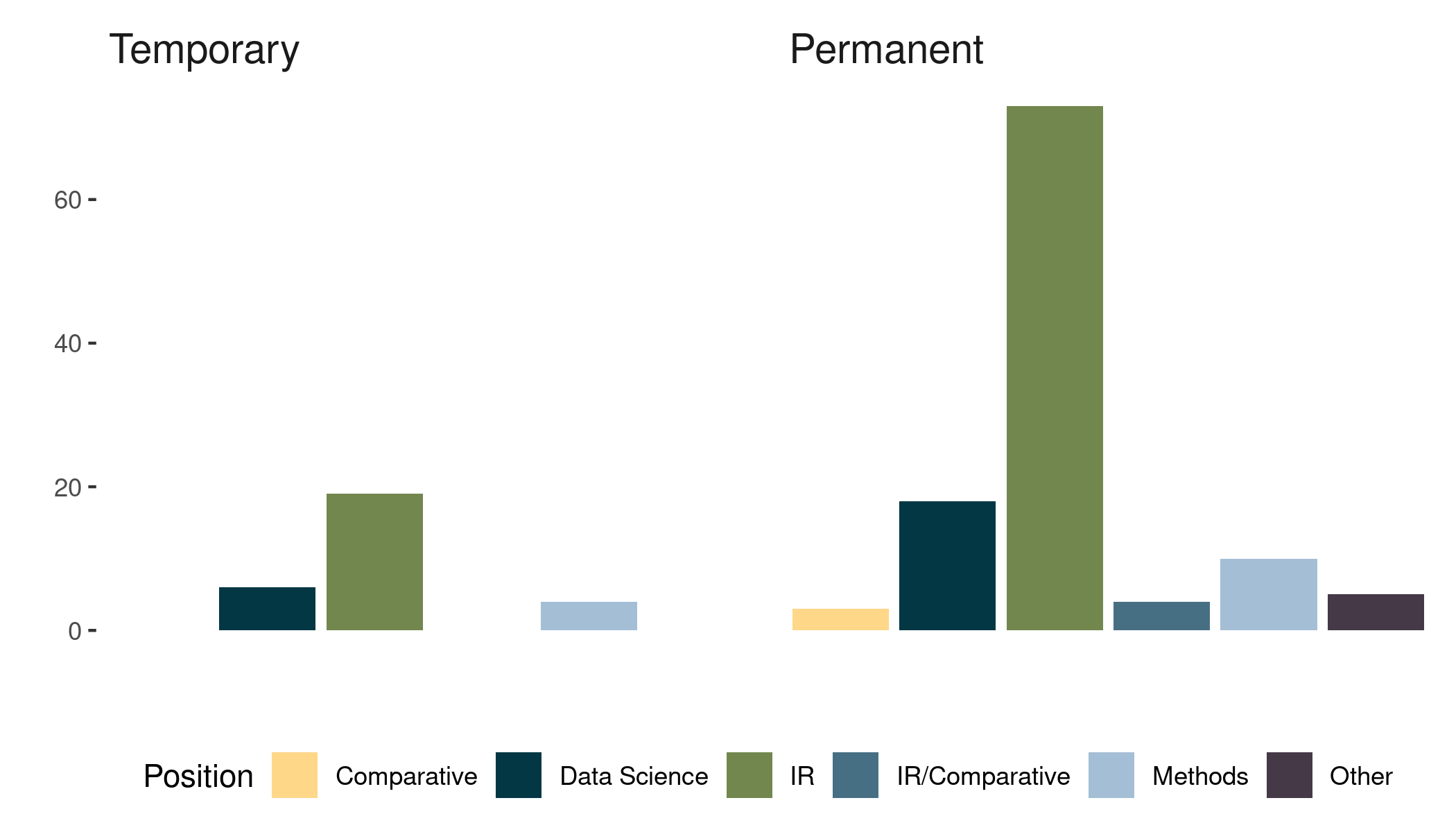

If we break down the jobs I applied for by academic subfield, some unsurprising patterns emerge. Data science jobs include those listed as computational social science, jobs listed for a substantive subfield and methods are coded under the substantive area, and international relations, conflict, peace studies, security studies, and international political economy are all represented in the IR category.

The majority of jobs I applied to (92) were advertised as international relations. While much of my research sits at the intersection of international relations and comparative politics, very few of the jobs I applied to do. I didn’t track how frequent these jobs are, so it could just be a case of few jobs to apply to. Data science (24) handily outnumbers the more traditional subfield of methods (14), reflecting increasing interest in the former by the discipline.

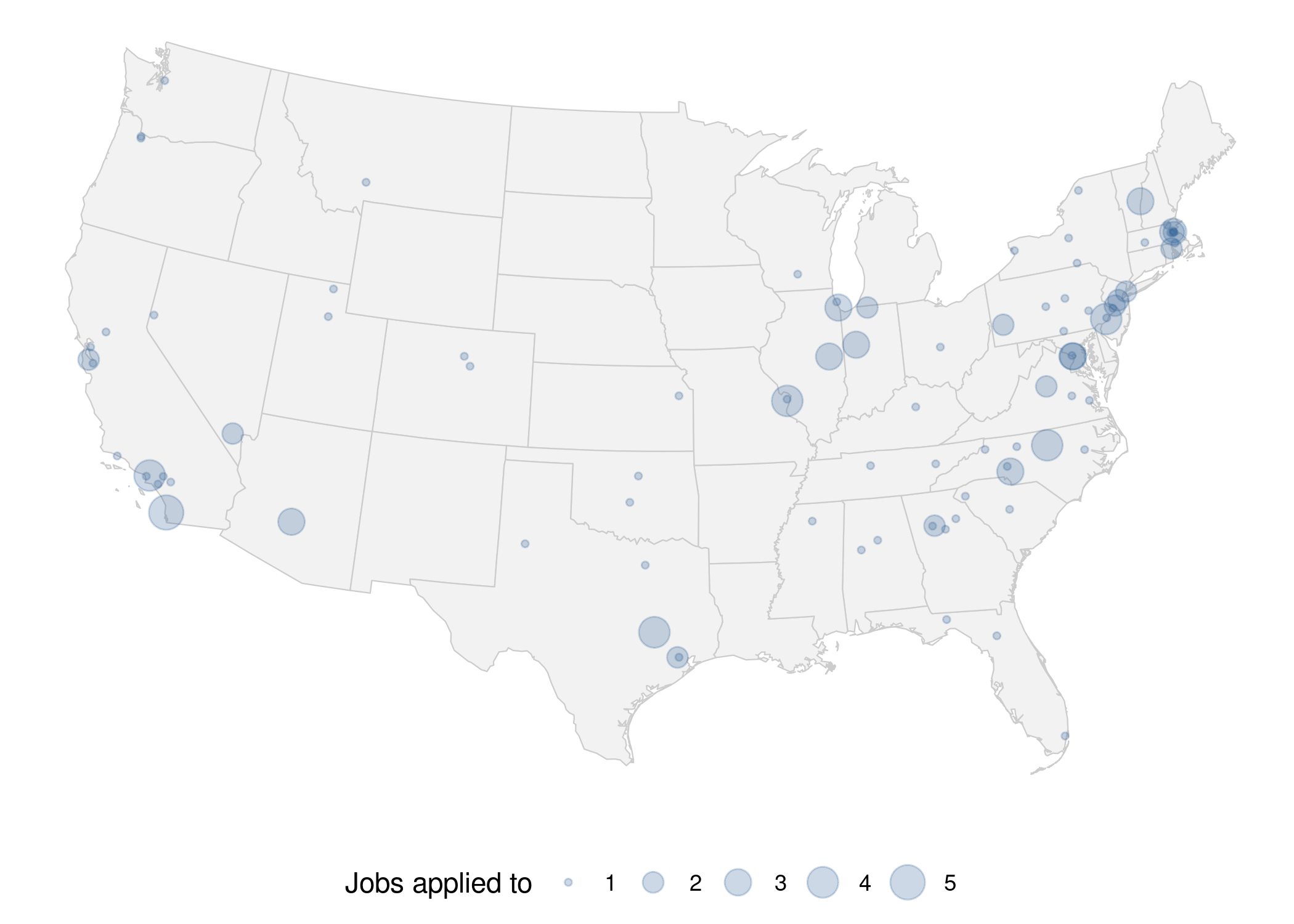

The map below geographically visualizes the jobs I applied to. Each circle represents one institution, with the size of the circle denoting how many positions I applied for. I applied to five positions at UCSD, the most of any institution.

I focused primarily on the Eastern US and California. I applied to jobs in 31 states and the District of Columbia, meaning there were 19 states I did not apply to any jobs in. Looking at my applications over time helps tell the story of my academic job search process.

The 2018-19 academic job market season was my final year of grad school. I wanted to be done, so I applied to a wide variety of jobs. The postdoc I received an offer from was actually the last position I applied for in this cycle. I was a little more selective in the 2019-20 job market season because I had an excellent postdoc, with a high chance of a second year of funding. I started a new postdoc in 2020 and knew that I had a second year of funding guaranteed. COVID-19 absolutely devastated the job market that cycle as well. With a second year of funding secure and precious few institutions hiring, I decided to spend my time focusing on improving my CV and applied to a total of four jobs that cycle, all tenure-track. The market somewhat recovered in the 2021-22 cycle, but there were still far fewer jobs than in my first two cycles. I applied to 19 jobs this cycle, all of them permanent. There were some great postdocs this cycle, but three years as a postdoc had been enough for me.

Two jobs did show interest in me this last cycle, but it was too little, too late. I had an offer for a data science job when I received an on-campus interview for one job, and had already accepted the offer when I received a Zoom interview for another. Given the typical pace of an academic search, it was possible that even if I were successful in getting an offer for either of these positions, it wouldn’t be for another month or two. My postdoc ended in June, and an offer in hand doing interesting research was an easy sell compared to that uncertainty.

Across all 142 applications, I ended up submitting 399 letters of recommendation to search committees. I was very fortunate that UNC has a department administrator handle letters for grad students as a sort of discount (read: free) Interfolio Dossier service. They generously provide this service to graduates of the department until they secure their first permanent job, even after they have left. I spent so long on the academic job market that I had no less than three different people help me with this process. I am incredibly grateful for their efforts and want to highlight the support they gave me.

I haven’t done as good of a job tracking my applications to nonacademic jobs because the process is much less structured and standardized. Some applications require a cover letter, so I can count up all the cover letters saved in my job search folder: 25. You can also apply for many jobs with just a résumé. Let’s say I applied to 10 of those, which makes 35 applications total.

I started the interview process with seven of these employers. Acknowledging some uncertainty in the denominator, that’s a 20% response rate, more than six times higher than my academic response rate of 3.5%. I completed the interview process with four of these employers, receiving one rejection and three offers (I withdrew from the other three interview processes after accepting one of those offers). A 75% interview success rate is pretty incredible compared to my experience on the academic job market. That’s an overall success rate of 8.6%, which is also more than six times higher than my overall success rate for academic jobs.

Or is it a 50% success rate? I actually interviewed for two different positions with two of these employers, so you could also slice the data less favorably and say I received offers for three out of six positions I interviewed for. That’s still an overall success rate of 8.1%, which is pretty damn good in my eyes. I also want to highlight some of the experiences I had on the nonacademic job market that I can’t imagine ever happening on the academic one:

- Recruiters reached out to me to ask me to apply to positions

- One employer alerted me to another position they were hiring for and connected me with the hiring manager for it

- Another informed me that I was actually overqualified for the position I applied for and considered me for a more senior position instead

- I had my first job offer almost exactly three months after I started my nonacademic job search in earnest

- I received three job offers in three days that week

Others have written extensively about why you shouldn’t view a nonacademic job as a backup option or a failure, but sometimes it’s just nice to know that people want to pay you. If you’re striking out on the academic job market, there are plenty of other options out there. So it goes.

-

People have criticized the term quit lit for focusing on the individual and ignoring the systemic forces that contribute to many people’s decision to leave academia. I am very persuaded by this argument, but no one has yet coined a similarly catchy and succinct alternative. ↩

-

I’m using the term nonacademic instead of industry, which is usually presented as the alternative to academic jobs for people with a PhD, because I applied for jobs in both the private and public sectors. ↩

-

I considered Kilgore Trout’s intended epitaph from Breakfast of Champions as a title for this post, but decided it was both too obscure and too bleak: he tried. ↩